Decisions, Constraints, and Tradeoffs

In a world where you can build anything, what will you decide to build?

How does a software product get built?

Often, someone has an idea. And then they embark on the painstaking task of transforming their idea into something tangible, working, and real.

The hard part about building a tech product is that there are no physical constraints. If you’re in manufacturing, you are constrained by the supply chain of raw materials, the machinery you use, your labor workforce, and unfortunately, the laws of physics.

These same constraints do not exist in software.

When you set out to build a tech product, you have nearly unlimited flexibility on how to build it. You can choose any programming language and still make it functional, you can choose any library and still make it pretty, and you can choose a style and make it look and feel however you want.

While there may be technical tradeoffs, what is possible to build with software is only limited by the imagination. And time.

Given that every feature needs to be designed, architected, and coded, it takes time to build a product. If you want to make sure your application is well tested, your user flows are well structured, and things “just work” as intended, that requires a degree of precision and coordination across a number of teams, both engineering and product.

With time being the constraining factor, you must make tradeoffs on what you can build. You may have to sacrifice one feature for another. You may have to sacrifice user experience to make it simpler from a technical perspective. And you may have to cut the scope of what you plan to build because it will simply take too much time.

In a world where you cannot build everything, what you decide to build matters.

A product is just the result of a thousand micro-decisions. From user experience decisions such as “what should the welcome screen look like?” to more technical choices including “how should I store this data to make sure a user doesn’t notice the latency?”, each decision you make adds up to create what we call a software product.

And when you’re building software, you often don’t realize how many micro-decisions you have to make. These decisions are everywhere. If you’ve read my posts on social proof, why the user is always right, and making it easy to use, I hope you’ve realized how many decisions go into building good products. Decisions such as:

How do I want it to work? How can I accomplish it from a technical perspective? How should I model the data? What should the user flow look like? How will I handle errors? How will I make sure a user understands the product? How will I maintain what already exists and still add the new feature?

And even after considering all of these practical questions, there are the questions about technology as a work of art. What do I want people to feel when they use my product? Should it be purely functional or should it spark joy? How can I make someone feel great using this product? How can I pleasantly surprise people so that it is not just a tool, but a part of their identity?

Making a brilliant piece of software is incredibly hard, but there are some tools that truly accomplish that. Sometimes, the decisions come together in perfect harmony, balancing all of the tradeoffs, making it easy for users, following all of the right patterns, and it just works. The product does the thing that it’s meant to do. And it does it well.

Two of my favorites are Hey for emails and Linear for product management. These two tools not only accomplish what they mean to, but they do it in a technical way that is satisfying and intuitive.

Some teams have north stars, which simplifies the decision making process. It gives a set of heuristics that allow the tradeoffs to become automatic. Some teams value having zero bugs, so when a new one is found, they drop everything to fix it. Some teams focus solely on the user interface, and are okay shipping new features with some bugs. These heuristics shape the team’s culture, and allow for easy decisions when things come up.

Once you have built and released a product, it takes on a life of its own. How people interact with it and how it becomes embedded into their routines is out of your control. The only thing that matters is all of the decisions you made. And unfortunately, for good or bad, each of your decisions comes with consequences.

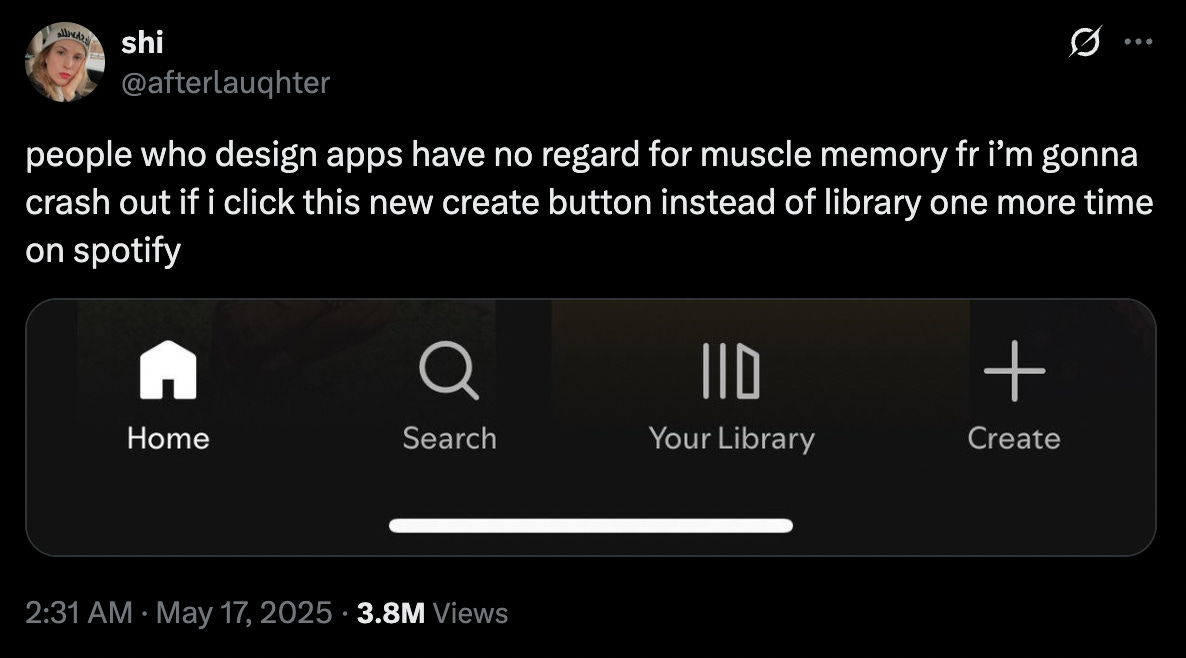

A decision can be a simple, innocuous change that consequently hurts the user experience, such as this week’s change to the Spotify tab bar:

While it may seem intuitive to always just build new features, adding more to a product is not always better. There are plenty of examples of products that got worse the more they added. I miss the old days where Slack was just a chat app, not trying to be a “AI workflow” company. I miss the days where DoorDash just delivered food. I understand why they changed these apps. They wanted to build more features to get more market share or entice more customers with “more”.

But each decision they made as a company affected how the product looks and feels today. Slack is no longer just a magical chat interface, it tries to be your workflow hub. They made the decision to build things like canvases and lists as opposed to focusing on the features that people used. DoorDash no longer just tries to help you find good food, it tries to deliver anything to you1. They made the decision to build several features and clutter their homepage, to the point where it’s actually more difficult to find new food to try.

On the flip side, Uber’s decision to change their home page to a single “Where to?” input was perfect2. They decided to double down on their main feature: to get you from where you are to where you’re going. What appeared to be a small decision actually made a huge difference. While they have added several new features to the app, it has never been at the expense of their core feature: to get you somewhere.

The moral of the story is that no matter what you decide to build, your decisions and tradeoffs end up defining the product.

So the question remains, in a world where we can decide to build anything, what should we build?

Should we spend months building the big new feature or should we take time to address some small, widely requested features? Should we enter a new space or should we stay focused on our niche? Should we spend time upgrading the technology or should we focus on fixing bugs?

There are constant tradeoffs when building a tech product, and it is often more important what you choose not to build than what you actually choose to build. By choosing to build a feature, you are saying no to many others.

At a startup, or really whenever you’re building a product, you are making a series of decisions with incomplete information. In an ideal world, you’d have the answers to “what will my current customers find valuable?” and “what will entice more people to try the product?” and “what will prevent user churn?”.

The reality is that you don’t know until you build something and put it out there. You can guess, you can speculate, but you won’t know how something lands with users until you decide it’s good enough to put in the hands of users3.

You have to rely on the time constraint, decide what you are willing to sacrifice in the product, and use the north stars you develop to build a product that aligns with your goals and user expectations.

I’ll leave you this week with an example of a decision to not build a feature. When I was revamping Split It, I got a lot of feedback from my friends who thought I should make an admin interface, where one person could assign items and then send Venmo requests without their friends ever interacting with Split It.

When I first started the revamp, I made the decision that splitting the bill should be social, transparent, and fun. This became the north star for every subsequent decision I made, and eventually, through these many decisions, Split It became a “Social bill splitting app”.

The idea to build an admin interface, while logical and probably useful to some, would have fundamentally changed the way people use the app. It would have contradicted my prior decisions, and changed the ethos and experience people had using it, straying away from the decision to make it fun and social4.

While building this one feature may not have been detrimental for my little app, it felt important to me to stay true to the north star. And having just crossed 1,000 checks split on the app this week, I am glad I stuck with my decision.

As you can see, when you can build anything, the little decisions really make a huge difference.

Until next week,

Cory

I would be so curious to see metrics on how many people like these large changes, vs. those who still use these products because they were already locked into the ecosystem.

Before, you had to enter both a “to” and a “from” when calling an Uber. They realized that people were often just entering their current location for the “from” field, and decided to use that as the default. They revamped their whole UI around this concept, and it remains the default way both Uber and Lyft operate today.

Yet another hard decision to make when building. When is it good enough? There’s only one way to know.

I think the place apps like Splitwise and Tab went wrong and didn’t get traction were because it’s “one person’s responsibility to get their money back” when in reality it should be everyone’s responsibility to pay the person back. They are taking a risk by putting their card down and they should not have to deal with that risk alone. I may get around to building the admin view at some point, but I think for now I want to lean into building features that makes it easier to split a check socially.